China-EU Brandy Dispute: Some evidence from past wine and spirits trade weaponization

Surveying some recent work (including mine) on trade restrictions including sanctions relevant to alcohol trade to help unpack recent Chinese rulings on EU brandy

A small plug: Join me for a South African wine tasting in NYC on 9/12: A fun night in support of the Heart and Soul Charitable fund that supports many community programs in NYC. find out more or reserve your place here or by emailing me.

This week, China’s customs agency determined that EU-made brandy is being subsidized to the tune of 30-39% and is thus being dumped on to the Chinese market. The decision was not a surprise given the timing of the initial investigation which came just after EU began to investigate and impose tariffs on several Chinese clean energy technologies. So too, was the decision by China to hold off on imposing any compensatory anti-dumping measures for now. This may reflect Chinese desire to negotiate on some of the other pending investigations.

This news seems a good time to survey a few recent studies that look at the trade restrictions on wine and spirits trade, including several good papers that were presented at the recent July 2024 American Association of Wine Economists Conference. I was excited to see a lot of great work being done on the impact of sanctions on Russian alcohol trade, the impact of US and Chinese tariffs on wine markets (and I’m not just talking my own book!)

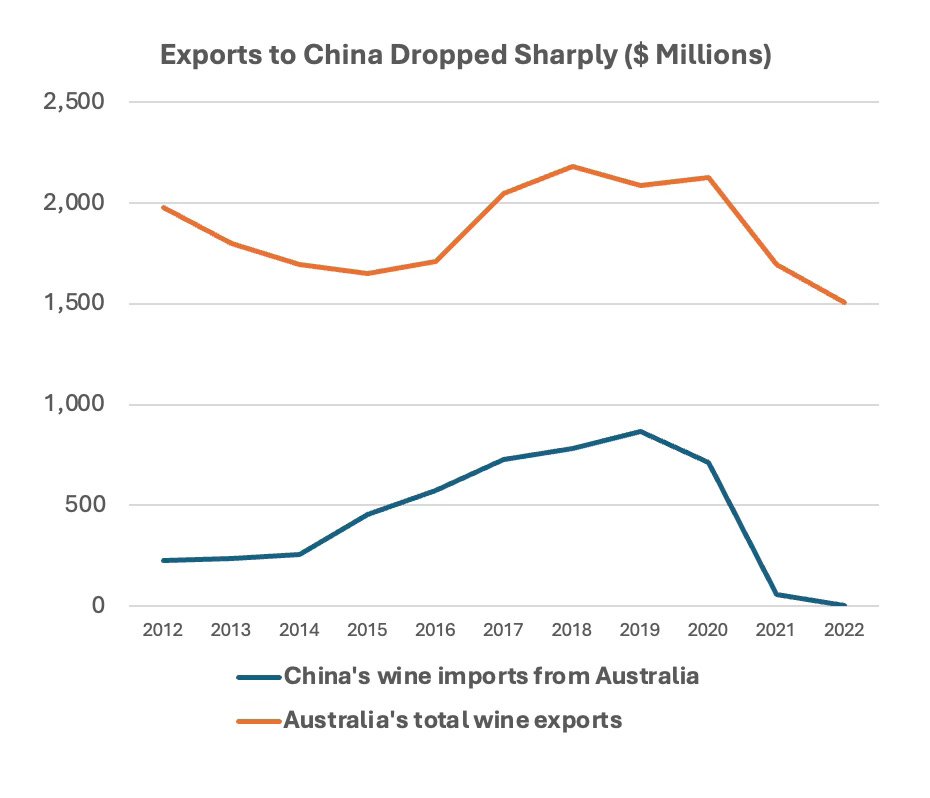

Some context: This is far from the first time that China has used tariffs or other trade restrictions on wine and spirits. Most recently, China imposed tariffs of up to 220% on Australian wine imports from 2020 until early 2024, contributing to a sharp decline in Australian exports of wine, which fell to 2% of their prior average.

China is far from the only country to use tariffs on alcohol products in implicit retaliation for other trade offenses or for competition within the sector. My past work mapped three phases/drivers of trade disputes on wine and spirits including:

– technocratic disputes, usually over preferential or discounted access for locally produced alcohol over imported ones (eg cases brought against, Japan, Korea, Ukraine etc over spirit subsidies or Canada over supermarket access)

- Formal compensation for anti-dumping or other disputes in non-alcohol sectors (eg US tariffs on EU wine in the Trump admin)

- Economic coercion implicitly or explicitly for national security goals (Russian bans on Moldovan or Georgian wine and perhaps Chinese bans on products for sanitary excuse)

Today’s move is likely a combination of these goals. While China customs investigation found collusion and dumping perhaps due to concentration of EU brandy production, the timing of the trade review and findings are too close to EU anti-dumping measures to be a coincidence. That they have yet to announce penalties or compensatory tariffs, reinforces the fact that China may view this as a negotiation tool with both countries opening up a range of anti-dumping moves. It also seems to be an attempt to drive a wedge between different EU members.

Research highlights that market actors are good at finding loopholes around alcohol and other tariffs and that sanctions and tariffs encourage relabelling, use of intermediaries and indirect trade, something I track a lot in my sanctions work (on the other blog and newsletter).

Work by NYU’s Magdalene Siao and Karl Storchmann bears this out. Their study looks at wine exports from Europe to the US in the time of tariffs on European table wine. The tariffs, compensatory ones from the Boeing -Airbus disputes, kicked in only on wine with 7-14% alcohol, since historically most table wine had alcohol levels 14%. Now with climate change, trends have changed of course and many Italian, French, Spanish wines push that limit and above. Suddenly Siao found that the share of French wines that had alcohol levels over 14% was much higher in the period when they would be exempt from tariffs. Before the tariffs, if anything producers rounded down the alcohol content. By contrast, there was less rounding up or higher alcohol reporting in Germany. This may not reflect German rectitude but rather with many exported wines of low alcohol, rounding up is just not plausible when it is more than 1 percentage point. The decision by producers is logical, but instructive.

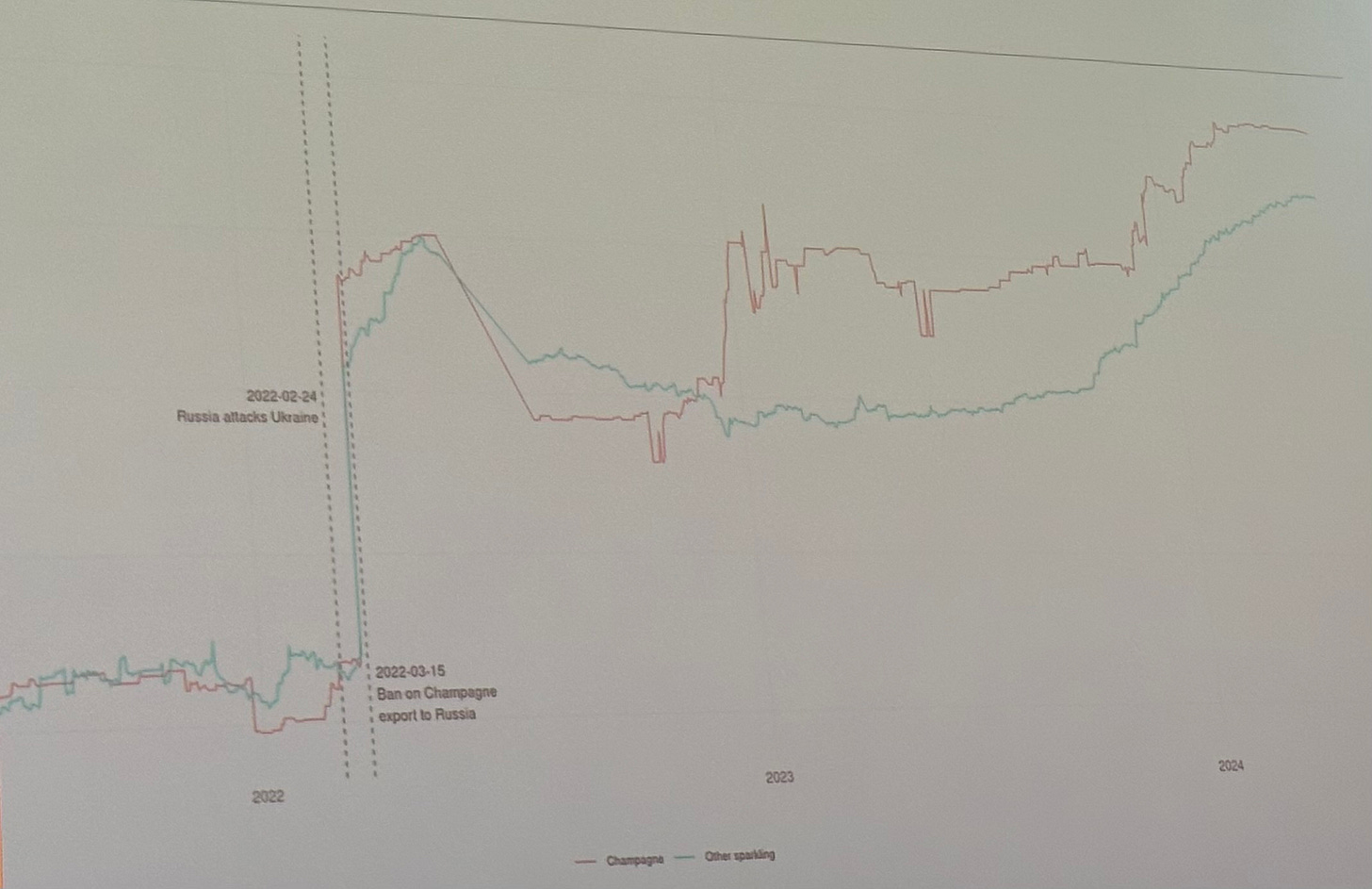

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and associated sanctions also led to distortions in the wine and spirits market between the Russia and the sanctioning countries in the global west. The EU quickly banned champagne exports to Russia (a luxury good that they hoped, in vain, would prompt rich Russians to pressure for policy change), but allowed exports of other wine and alcohol. Reports from consumers in Moscow suggested that French Champagne continues to be available in supermarkets, unsurprisingly at a premium. Work by Mengting Yu of the University of Tuscia utilizes online data to show some of these price premia in another example of the extensive additional data available to economists.

Even goods that were not subject to sanctions or bans show signs of more indirect trade as I pointed out in my paper. Russian imports of wine from the European Union have fallen only modestly from early 2022 through early 2024, but the source has shifted. The great wine producers of Latvia and Lithuania now account for higher export volumes and revenues that those from Spain, Italy and France combined. Undoubtedly, it’s easier for those major producers to sell through intermediaries closer to the Russian border even in cases where theoretically trade is legal even if actual payment mechanisms are hard.

Returning now to China, and the potential tariffs on European brandy. The recent experience of Australia was painful, cutting exports and revenues sharply. Contrary to what one might expect from a major distortionary trade measure, few of Australia’s competitors could benefit. Around the same time Chinese consumption and imports of wine collapsed from all over the world, after peaking in the mid 2010s. This followed anti-corruption and anti conspicuous consumption crackdowns brought in by Xi Jinping. Almost all major wine producers (aside from New Zealand and Germany) experienced sharp falls in exports to China. While Australia was the worst hit, France, Italy, Spain also experienced major declines, with exports to China falling to around 50% of the level of the prior five years. Chinese demand collapse has reinforced more modest demand easing globally.

The story for brandy might be supported by somewhat more resilient spirits consumption, but its unlikely to be immune from both sluggish Chinese consumption, and EU-China tensions that may detract from EU products. This suggests that even in the absence of actually implemented tariffs, Cognac sales will likely suffer. However, it’s hard to see Europe yielding to coercion at least coming from alcohol sales, but that’s a topic for another time and place.